Edwin L. Kendig Jr.: Difference between revisions

Migratebot (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Migratebot (talk | contribs) Fix image duplication and formatting issues 🤖 Generated with Claude Code |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

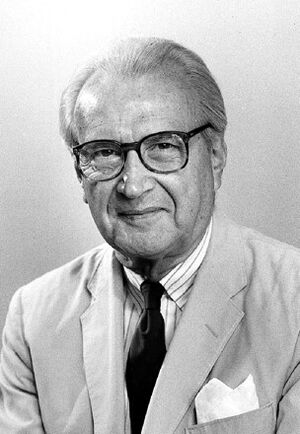

[[File:Dr. | [[File:Dr. Edwin L. Kendig.jpg|right|thumb||Dr. Edwin Lawrence Kendig, Jr.<br>|American Academy of Pediatrics]]<br>'''Born: '''1911 | ||

'''Died: '''2003 | '''Died: '''2003 | ||

Latest revision as of 11:07, 18 September 2025

Born: 1911

Died: 2003

Children: Anne Randolph Young, Mary Emily Corbin Rankin

Married: Emily Virginia Parker

Dr. Edwin Lawrence Kendig, Jr., is considered one of the founders of pediatric pulmonology. Following his own experience with tuberculosis, treated at Trudeau Sanatorium, he opened a 'chest clinic' for children in Richmond, Virginia, where he worked for fifty years. He systematically published his observations and was the original editor of the first textbook in pediatric pulmonology in 1967. His book, now called Kendig and Chernick's Disorders of the Respiratory Tract in Children will publish its 9th edition in 2018. All of this was in addition to his primary care pediatric practice, his teaching and his work at the national and international level of pediatric care. In his lifetime, he received many awards, including the establishment of the annual Edwin L. Kendig, Jr. Award from the American Academy of Pediatrics given for lifetime achievement in pediatric pulmonology.

The following memoir was written by Edwin L. Kendig Jr., M.D., c. 1996

The Great White Plague: a Personal Memoir

Only a few physicians today remember tuberculosis when there was no available antimicrobial therapy. In the 1940’s, tuberculosis was still among the most feared of all diseases, the great white plague. While the prognosis had improved over that twenty years earlier, the disease ranked in degree of severity with cancer, heart disease, and stroke.

Treatment of Tuberculosis at that time consisted primarily of bed rest, accomplished in the United States mainly in more than 400 sanatoria scattered throughout the nation, and situated most often in the mountains and in the arid climate of south-western states. When, in 1942, I was called for active military duty, my chest roentgenogram revealed changes compatible with active pulmonary disease. I became a patient at Trudeau Sanatorium.

Trudeau Sanatorium in 1942 was the prototype of the sanatorium of the day, a 200-bed facility situated on the periphery of Saranac Lake, a small town in the Adirondack mountains, near the Canadian border. It was a beautiful area -- a land of rolling hills, lakes, and nearby mountains. Under ordinary circumstances, it was just the spot for a pleasant vacation, and, indeed, the Lake Placid Club, Whiteface Inn, and other resorts were nearby.

The sanatorium itself consisted of a number of buildings, highlighted by the handsome and commodious main building that served as both social center and dining area for ambulatory patients. In addition to Ludington and Childs Infirmaries for those patients whose disease had progressed to a life threatening stage, there were cottages for ambulatory patients, as well as others for those whose serious disease required complete bed rest. There were other buildings, among them the chapel, the library, the nurses’ residence, radiology, Alma Pierce’s workshop for occupational therapy, and a special cottage for patient admissions.

The beauty of the country and the magnificent sanatorium complex, however, made little impression on me. I had a disease for which there was no cure. I might survive, perhaps even maintain a life-style of limited activity, but the odds of full recovery and of fatal outcome seemed just about even. It was not a comfortable feeling.

After I had spent a week in the admissions cottage, my disease was evaluated as follows: no disease was apparent in the right lung; the left lung showed lesions compatible with active pulmonary tuberculosis, with possible early cavitation. It was determined that I should have strict bed rest and artificial pneumothorax. I was assigned to Loomis, a “down cottage”.

Loomis Cottage was a small shingle and clapboard building, with four bedrooms, a couple baths, and a large central room that served as both a dining and sitting area. These rooms were not subject to overutilization; therapy for tuberculosis in 1942 dictated fresh air and rest, and that was the program. Four patients were assigned to Loomis; the four beds were in place on the large front porch, and the patients were instructed to stay there.

The “tray boys,” who to us seemed ancient (remember, this was war-time, so they were probably fifty years of age), brought meals, and we assembled indoors for these occasions. The “tray boys” also served in a general factotum role, with duties such as destroying huge icicles that seemed to hang from the cottage roof regularly. Except for meals and trips to the bathroom, patients were supposed to rest in bed and on the porch.

Much has been written about Saranac Lake “cure chair,” described as an ingenious hybrid of chaise lounge and hospital bed, but I do not recall much about it. I well remember the hospital bed, as well as a primitive electric blanket, parka, and gloves. All patients had a small personal radio. Prescription for cure was rest (and freedom of care), so reading was allowed, but not encouraged. Television was in the distant future.

A few days after my arrival at Loomis Cottage, winter arrived with a bang. It snowed-- and snowed. For me, fresh air was fine in its place, but I was not ready for the extreme cold. I paid one of the “tray boys” fifty cents to move my bed back indoors. In my mind’s eye, I can still see the physicians on their daily rounds, and hear them saying,”You ought to be out in the fresh air.” They were never able to coax me out again. Fresh air reached me through a partially opened window.

Treatment

My treatment regimen had been dedicated: bed rest, relaxation (freedom from care), and artificial pneumothorax. The first was not too difficult. I did not feel like bouncing about. Time helped in the promotion of relaxation, both of body and mind. (One of the “inside jokes” among patients was: “You see that new fellow out there? No, he’s not a patient; he looks tired.”) Artificial pneumothorax posed something of a problem. This procedure was accomplished by the injection of a measured amount of air into the pleural space, the pressure thereby compressing and collapsing the lung. The affected lung was thus put at rest, and the theory obtained that the diseased area would then have a better chance to heal. My hung would not collapse; adhesions, presumably the result of earlier pleural inflammation, prevented it. For the pneumothorax to be effective, the adhesions had to go.

Trudeau had no provisions for surgery, so all such procedures were accomplished at the Saranac Lake Hospital. Thus, early one morning, I was guided into a taxi and transferred to that hospital. Sometime later in the morning, under local anesthesia, the surgeon, Ed Wells, severed the adhesions (pneumonolysis), and I was returned to my room, where I spent a glorious afternoon floating in a semiconscious haze.

The next morning I was back in the taxi to Trudeau. On arrival and pursuant to earlier instructions, I went directly to the X-ray department for follow up films, then back to Loomis and to bed. About thirty to forty minutes had passed when two staff physicians came rushing into my room asking, “Are you all right? Are you all right?” Yes, I was fine. It seems that the increased pressure resulting from the pneumothorax had been contained by the adhesions. When these adhesions were released, the sudden increase in pressure caused complete collapse of the lung (on x-ray examination, the left lung resembled a rumpled handkerchief), resulting thereby in displacement of the [[1]]. Such a sudden mediastinal shift often had resulted in respiratory embarrassment and may even be fatal. I had no problem.

Parenthetically, it might be added that the artificial pneumothorax at first requires frequent refills as the pleura gradually thickens, however, the necessity for refills is reduced to two-week intervals. Bed rest was the basis of treatment of Tuberculosis during this period, and artificial pneumothorax was the most popular, and, presumably, the most effective adjunct. Pneumoperitoneum and phrenemphraxis (crushing of the phrenic nerve) were other less commonly utilized methods of putting a lung to rest. Other forms of adjuvant therapy also were designed for advanced disease that involved one lung. One such was thoracoplasty, a surgical procedure by which portions of the ribs covering the affected lung were removed so the lung remained permanently collapsed. Another procedure dealt with a disease cavity that showed no inclination to heal. For this condition, the Monaldi procedure utilized a catheter leading from the cavity to a suction apparatus located outside the chest wall. There were others. In my own case, I received artificial pneumothorax treatment for five years.

Progress

In spite of the serious nature of my infection, I had little cough, and tubercle bacilli in my sputum were never demonstrated. Determination of my disease status depended, in addition to the above, on my general physical condition, and included appetite, weight gain or loss, and the appearance of lesions on chest x-ray examination. After about three months, I was deemed a candidate for ambulatory status.

The sanatorium routine for advancement to ambulatory status was strict: a fifteen minute morning, and afternoon for one week. Activity for the second week was increased to thirty minutes twice daily, and for the third week, forty-five minutes morning and afternoon. If no untoward symptoms had appeared when the one-hour level was attained, “up-patient” status was achieved, and the only limitation of activity consisted of a compulsory two-hour rest period following lunch. The patient was allowed to have meals in the dining room. Indeed, he (she) could take a taxi into Saranac Lake for shopping, browsing, or an occasional dinner. To combat severe cold, raccoon coats were available. I achieved ambulatory status without incident, and soon afterward was transferred to James Cottage, a much larger building also referred to as the “Doctors’ Cottage,” since it was occupied entirely by patients who were themselves either physicians or medical students. Indeed, this one cottage was not large enough to accommodate all the physician-patients. In the 1940s, tuberculosis was for physicians, medical students, nurses, and nursing students an occupational disease.

Ambulation

With meals in the dining room, the patient was afforded the opportunity to meet other patients. This contact led to low-key socializing -- a dinner in town, an occasional picnic at the lake. It also led to friendships, most of which lasted only for the time spent at Trudeau. We were all in the same boat, sheltered from the outside world, but far from content and with one primary goal-- to return to the outside world and active life. Ambulation was one step nearer to a return to active life, where all these months (and for some, years) could be forgotten, or at least be put into proper perspective.

The Staff

I have read somewhere of the large medical staff at Trudeau, but I remember only a few. Fred Heise was the medical director and seldom seen by patients. George Wright, a physiologist, was one of the researchers. But the medical staff as seen through the patients’ eyes consisted of Spencer Schwartz and Bill Richardson. These two made regular patient rounds and were always in evidence. There were others, of course. As the physician-patients recovered, they were usually recruited for part-time duties; but Drs. Schwartz and Richardson were two regulars.

There were also two particularly interesting staff members. Homer Sampson was the radiologist, and how he attained the position is a fascinating story, perhaps exaggerated. Sometime after the turn of the century, when diagnostic radiology was in its infancy, an x-ray machine was acquired for use at Trudeau Sanatorium. What was there to do with it? No one there had expertise in that specialty. So Dr. Trudeau or whoever was in charge at the time, looked for someone to take charge of the x-ray department. The choice was Homer Sampson, one of the patients. Sampson has not attended medical school, and indeed, one version of the story identifies him as a shoe salesman. Nonetheless, the choice was a good one. Homer Sampson became a diagnostic radiologist, and grew with the specialty. When I was a patient at Trudeau, Sampson was an elderly man, with a shock of white hair and a rolling gait, who seemed completely in charge. And he was. I remember seeing ancient X rays on glass plates, and I particularly recall large packets of x-ray film, postmarked from some industrial plant or complex, sent for Homer Sampson’s reading and evaluation. He had achieved national, perhaps international recognition ,

The other permanent non-medical member of the staff was William “Bill” Steenken. When Bill’s father developed tuberculosis, he moved with his family to Saranac Lake. Bill was a college student at that time. He later began to assist Dr. Petroff in the laboratory, and at the time of my stay Bill had become director of the laboratories, and an excellent researcher.

Physicians as Patients

Statistics as to the number of physician-patients at Trudeau Sanatorium during the period are not available, but if memory serves me well, there were about twenty to twenty-five physicians and medical students. As might be expected, the reaction to the disease and to the Trudeau experience varied with the individual physician-patient; such reaction, however, did not always equate to the severity of the illness.

When I arrived at Trudeau I was devastated. It was difficult for me to adjust to the sanatorium approach, an example of which was my move indoors when the snows began. After a brief period, however, I was able to relax, and almost completely, without losing my perspective. While I do not wish to repeat the experience, Trudeau was a great teacher; it taught me patience, humility, and understanding. I learned the patient’s viewpoint. Finally, Trudeau and sanatorium changed the direction of my career.

Life after Trudeau for physician patients took varied turns. Manny Wolinsky became a prominent pulmonologist; Henry Clarke, a medical educator; Frazier Parry, a physiatrist; Paul Downey, an obstetrician-gynecologist; and Walker Percy abandoned medicine completely and became an award-winning novelist. Is strict bed rest an outmoded therapy? Yes, there is no logic in it. The present-day approach, however, is not too effective, either. A way must be found to keep those with infectious diseases off the streets and to ensure that tuberculous individuals actually take prescribed medications. A return to the availability of tuberculosis clinics and more emphasis on direct observation therapy (DOT) would help.

Health departments must place more emphasis on tuberculosis control (more trained personnel, for example), both in case finding and therapy. Practicing physicians must become more aware of the disease, and the younger physicians must learn more about it. There is a need, too, for another effective anti-tuberculosis chemotherapeutic agent.

Finally, while I subscribe to the general opinion that mass tuberculin skin testing is nonproductive, I am one of the remaining few who is still an advocate of routine tuberculin skin testing for children, both in the practitioner's office and in health department clinics.

Conclusion

Sometime during my last months as a patient at Trudeau, I received a letter from Wilburt C. Davidson. This was wartime, of course, and Dr. Davidson, dean of the Duke University School of Medicine, had been recruited as secretary of the National Research Council. In his letter, Dr. Davidson offered me a position as his assistant, and I was ready to accept, with alacrity. The Trudeau hierarchy put that one to a rest in a hurry. “Washington is too hot; you will reactivate your tuberculosis.” (There was no air conditioning in those days.) So, I avoided discussion of the weather in Baltimore and went back to Johns Hopkins, as I had earlier planned. I wanted to learn more about pediatric pulmonology, a study of tuberculosis.

Over the past fifty years, I have continued my interest in the disease that almost finished me. I initiated and have directed a children’s chest clinic over that entire period and at the same time managed to make a career both in academia and private practice. As I approach my eighty-fifth birthday, I still play tennis. But I was one of the lucky ones.

And remember, the great white plague is back.

External link: